Computer graphics is linear algebra in motion. Every vertex, camera, and light is moved by vectors and matrices before a pixel is drawn.

This article is a practical guide. We will go from vectors and matrices to the full model‑view‑projection pipeline, explain why normals need special care, and show where most graphics bugs really come from.

You do not need to be a math major. You do need a clear mental model. That is what we will build here.

A 3D scene is a set of points. The job of graphics math is to move those points through a pipeline of coordinate spaces.

Most engines use this order: model space → world space → view (camera) space → clip space → normalized device coordinates.

clipPos = Projection * View * Model * vec4(position, 1.0)A vector can mean two different things: a point or a direction. The math you use depends on that meaning.

Points have position. Directions only have magnitude and orientation. This difference becomes important when you translate with matrices.

Dot product: angle and lighting

Cross product: surface normals and tangents

Normalize direction vectors for stable shading

Translation is not a linear operation in 3D. That is why graphics uses homogeneous coordinates and 4×4 matrices.

The extra w component lets translation and rotation live in the same matrix multiplication.

vec4 p = vec4(x, y, z, 1.0) // point

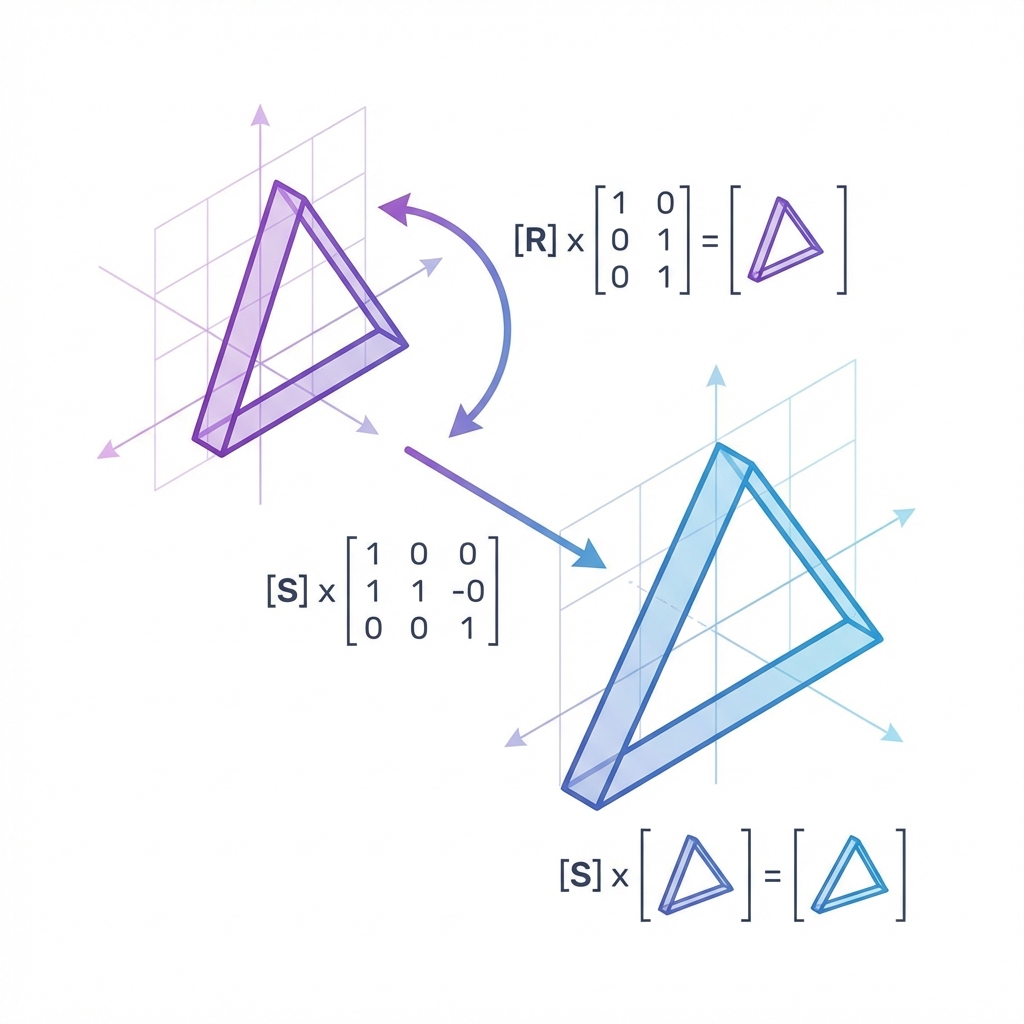

vec4 d = vec4(dx, dy, dz, 0.0) // directionMatrix multiplication is not commutative. The order of transforms changes the result.

If you scale, then rotate, then translate, your matrix order must reflect that exact sequence.

// Column‑vector convention (GLSL)

result = T * R * S * vThe model matrix moves local object vertices into the world. The view matrix moves the world so the camera is at the origin. The projection matrix applies perspective.

Once you see it as “where is the object” and “where is the camera,” the pipeline feels less mysterious.

Perspective makes distant objects appear smaller. Orthographic keeps size constant. Both are just matrices.

Perspective uses FOV, aspect, near, far

Ortho uses left, right, top, bottom, near, far

Normals are not positions, so you cannot transform them with the model matrix when there is non‑uniform scaling.

Use the inverse transpose of the model matrix to keep normals perpendicular to the surface.

normalMatrix = transpose(inverse(Model))

worldNormal = normalize(normalMatrix * normal)Diffuse lighting is just the dot product between the light direction and the surface normal. Specular highlights are also dot products, just with a different vector.

If your lighting looks wrong, check that your normals are normalized and in the right space.

Object moves the wrong way: check matrix order

Lighting breaks after scaling: check normal matrix

Camera feels inverted: check handedness

Everything is clipped: check near/far planes

A quick trick: render normals as colors. If they look wrong, the rest of your lighting will too.

Matrix math is cheap on the GPU, but it still adds up. Batch what you can and avoid redundant calculations.

Precompute static matrices

Use instancing for repeated meshes

Upload matrices once per frame, not per vertex

Try it

Why do we use homogeneous coordinates (4×4 matrices) in graphics?

Order the graphics pipeline transforms.

Drag and drop practice coming soon! For now, here are the items to match:

When non‑uniform scaling is present, how should normals be transformed?

Linear algebra is not optional in graphics. It is the language that moves every point and every normal through the pipeline.

If you keep a clear picture of spaces, know when you are working with points vs directions, and respect matrix order, most graphics math becomes predictable and even enjoyable.